The instrument most responsible for the advancement of humankind was the gnomon, also known as the carpenter’s square. The most advanced societies in early civilization could be associated with the use of the gnomon that in turn, would identify a functional calendar. As a result, the Egyptians and the Chinese would have the the most advanced agricultural communities that would lead to prosperity and evolution.

The first

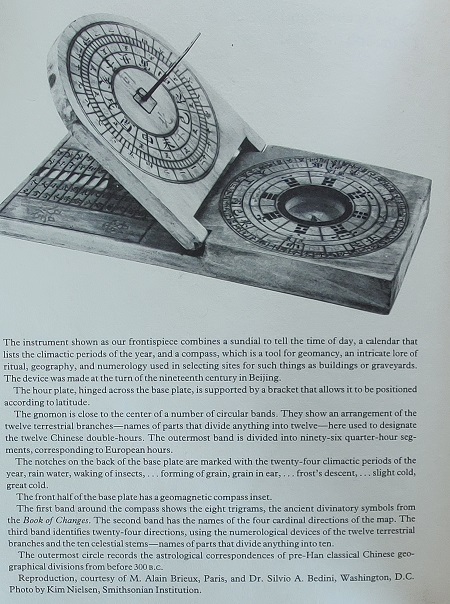

printed page of the wondrous Science and Civilisation in China (Joseph

Neeham, 1959) encapsulates the totality of early Chinese cosmology:

The

carpenter’s square is no ordinary tool, but the gnomon for measuring the

lengths of the sun's solstitial shadows.

The circle (heaven), the square (the earth), the measurement of time and space, and the astronomical instruments that help to connect humankind with heaven are important concepts that lead to the symbols used by the ancients in ceremony, art, and architecture.

The

carpenter’s square, or gnomon, was the first instrument to document evidence of

the sun’s light (and the resultant shadows), thus becoming humankind’s first

instrument for determining and preserving images of the passage (or numbers) of

time. The oldest known gnomon dates to about 3,500 - 2,300 BC (Egypt and China), sixteen hundred

years ahead of the Greeks and Western civilization. Prior to the gnomon, there

was no method of interpreting celestial signs, and time had no image to

measure.

The shadow became the image of the means to measure time, and thus from its first use, the upright gnomon enabled such measurement. The daily measurement of the shadow for thousands of years became a tradition of moral behavior etched into the daily lives of the early Chinese such that the instruments and mathematics involved became part of the symbols and numerology used in art, language, and ceremony. (from The Secret of the Magic Square, Robert Dickter, 2025).

Image

1. Measuring the sun’s shadow length at summer solstice with a gnomon and a

gnomon shadow template. (Image from Number Time Archetype, Robert Dickter, 2014).

The

carpenter’s square is symbolic of the gnomon and, in some cases, the two terms

can be used interchangeably. Its role in measuring the heights and distances of

the universe as well as an astronomical instrument that helps measure time make

the carpenter’s square / gnomon critical to the rise of civilization. The

carpenter’s square represents the wisdom of the right-angle triangle and evokes

the promise of establishing order on earth.

This is

why the symbolism of the carpenter’s square / gnomon plays an integral part in the origins of early

Christian art and architecture. The consistent use of this symbol demonstrates

the importance the early Christian hierarchy placed on the role of math and the

measurement of time.

Let us

know examine the use of the carpenter’s square / gnomon in art and architecture

throughout the history of an evolving civilization, whether it be in ancient Egypt, early

China, or the West.

Egypt, 1504 to 1425, BC

Early China, 140 AD to 689 AD

Image 3. Two examples of the legendary sage Fu Xi holding the carpenter’s square and

his wife / sister Nu-wa holding the compass. The example of the left was etched

into the walls of the Wu Liang tombs, c. 140 AD. The example on the right is

from a silk veil found in the tomb of Fan Yen-Shih, 689 AD, and again reflects

the image of Fu Xi and Nu-wa.

Fu Xi and Nu-wa are mythological characters that represent the first ancestors of the Chinese, a legacy that is over four thousand years old. The yin-yang relationship of the male who rules heaven holds the set square which represents earth, as the female who rules the earth holds the compass which represents heaven. In language, the Chinese character for carpenter's square ju, 矩, when combined with the Chinese character for compass gui, 規, forms a new word, gui ju, 規矩, which means to establish order, a moral code, or the way things should be. It literally means the compass and square. This might be the instance that the symbol for carpenter's square and compass evoked the concept of moral behavior as well as establishing order from chaos via the implementation of wisdom, or mathematics. The word gnomon in Greek also means "one who knows, a rule of faith or conduct". The Chinese word ju (chu) means gnomon / carpenter's square, a rule, pattern, usage, a custom. Both have similar meanings and concepts that relate the usage of an astronomical instrument that can identify the passage of time to wisdom and a moral standard. Ancient China began using the gnomon about 2300 BC.

The

Middle East

Cave of

Letters, C. 130 AD

The earliest usage

of the carpenter’s square (as a religious symbol) represented by the gammadia, from gamma, a Greek

letter in the shape of a right angle, is attributed to the Jewish religion. This

art motif would appear on garments found in a cave from the Dead Sea discovered

in 1966. In the Bar Kokhba Cave scrolls and many old and well-preserved

garments worn by especially holy initiates of the Jewish religion were

discovered. The art motif known as the gammadia would be used for hundreds of

years in early Christian art and architecture.

Syria

Dura

Europos Synagogue and Church, c. 245 AD

Here one

can find the coexistence of the Jewish and Christian communities in the Roman

world.

Image 4. Paintings on the walls of the Dura Europos synagogue demonstrating the gamma

or carpenter’s square motif on female garments.

Dura Europos was founded in about 300 BC, an ancient city on the Euphrates River in modern-day Syria. The city became a cultural melting pot of Greeks, Romans, Syrians, Jews and Christians before Christianity became the dominant religion.

The

Oriental Influence on Early Christian Art and Architecture

Theodoric’s Mausoleum, 520 AD

Image 5. Theodoric’s Mausoleum, Ravenna, Italy. The use of the carpenter’s square in

architecture with the names of the twelve apostles etched onto each right

angle.

Ravenna, Italy, 525 – 85O AD

Image 6. The carpenter’s square usage on mosaics, c. 525 AD. On the right, four

apostles and Christ blessing the loaves and fish, Sant’ Apollinare Nuovo,

Ravenna. On the left, The Sacrifices of Abel and Melchizedek, c. 540

AD, in the Basilica of San Vitale, Ravenna.

The gammadia

was used to identify people, architecture, or objects of religious importance. The

art motif was an important symbol that emphasizes wisdom (math) that

corresponds to establishing order, one who knows, and a moral standard. The symbol can be

found on garments worn by the especially initiated such as the twelve apostles,

books such as illuminated manuscripts, buildings such as temples and basilicas,

altar cloths, and mosaics that adorned the early churches. There are literally

hundreds of examples of this usage form the Middle Ages in dozens of churches.

Now that

we have established the origin and use of the carpenter’s square as an iconic

symbol, let us now look at some of the world’s greatest artists who recognized

the significance of the carpenter’s square as an example of Pythagorean

philosophy: that numbers, weight and measurement help to explain and bring

order to the material world we live in.

The Carpenter’s Square Used in Art, 1514 to 1919

Image 7. Albrect Durer’s Melancholia I (1514) with the compass, set square, and numerous references to mathematics and geometry, including the magic square, also a symbol of establishing universal order thru the implementation of math.

Image 8. Hans Holbein, The Ambassadors (1533) also demonstrating many references to math and astronomy. Note the carpenter’s square is holding a place in a math book by Peter Apian, A New and Well-grounded Instruction in All Merchants’ Arithmetic (1527).

Image 11. William Blake’s The Ancient of Days (1734) and Christ in the Carpenters Shop (1805) also emphasize religion and mathematical instruments that connect wisdom with the tools of geometry.

Image 12. Salvadore Dali’s Leda Atomica (1949) follows a strict mathematical template

that emulates the divine proportion (the golden ratio) featuring the carpenter’s

square once again.

Image 13. Detail of book. The cover exhibits quincuncial composition: the four corners are small squares representing earth, the five rectangles form a cruciform shape representing heaven, the center has the classic circle within a square representing the axis mundi, or the meeting of heaven and earth. The central rectangle meets the measurements that reflect the golden ratio, 1.6.

History

and wisdom merge when science and math are incorporated into art and

architecture. The early Chinese recognized this and used these concepts in city design, tomb design, and to identify buildings and things of political and religious importance. In this regard, the origin of early Christian church art and architecture

has a decidedly oriental influence. Artists throughout history have carried the

burden of educating the masses as to the importance of science and math. In

this way, the story of civilization lives on thru the use of symbols such as

the carpenter’s square, compass, and the magic square.