Introduction

For the benefit of those new to this site, this post will serve as an introduction to this blog and to my book, Number Time Archetype. Please understand that this is an ongoing effort that is now entering its thirteenth year.

Galileo once remarked that the world is a book written in mathematical language alluding to the theory that the mysteries of nature can be solved by simply examining the math. Throughout modern history geniuses such as Plato, Pythagoras, Da Vinci, Durer, Galileo, Newton, and Leibniz acknowledged that mathematics was necessary for the evolution and prosperity of humankind.

However, the world of math could only begin with the advent of numbers. Therefore, a numbering system would be the impetus of human evolution and prosperity.

Numbers are a language unto themselves at the ready to impart wisdom upon humankind for the purpose of evolving and prospering. The language of numbers would provide humankind with the tools and mathematical formulas to manage time and space: time as in the numbers of the calendar and space as in the Pythagorean Theorem. The arrangement of numbers into squares would reveal this information. These squares of numbers are called magic squares. The following represents the simplest magic square:

The Chinese 3x3 magic square known as the Luo Shu.

Note that all the rows, columns, and diagonals add to fifteen, the magic constant.

The gnomon was simply a stick in the ground whose shadow length would determine the approximate time of year between winter and summer solstice. The painstaking tradition of measuring, recording, saving, and studying the shadow length data for thousands of years, i.e. calendar making, was part of the moral standard to evolve and prosper and was essential to the role of the king. The shadow of the gnomon was in a right angle relationship to the gnomon thereby generating a right angle whose measurements would satisfy the Pythagorean Theorem. Therefore, the gnomon, the right angle, and the carpenter's square were symbols of time and space.

The gnomon, the Luo Shu (math and the concept of number), music, and astronomical tools had special status among the early Chinese as these were instruments that helped humans to connect with Heaven for the betterment of humankind. The Luo Shu was an important element of Chinese philosophy as it represented a musical source, an astronomical correspondence, and a mathematical system that enabled the Luo Shu to become a spiritual tool to establish order and bring humankind in harmony with Heaven and earth.

The secret to the Luo Shu is the following formula that allows expansion of the 3x3 magic square into larger magic squares that all exhibit features in common but the most significant is that a Pythagorean triplet of numbers appears at the heart of each square.

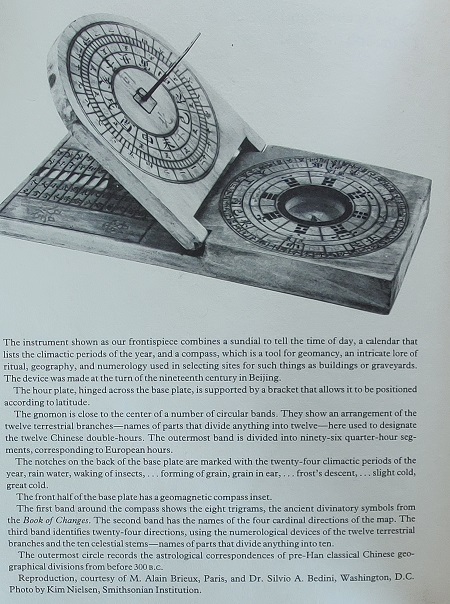

This book will reveal for the first time the influence of the Luo Shu on early Christianity. There is no question that monks from as early as the eighth century were incorporating magic square symbolism onto the covers of some of the worlds' most valuable books. This blog and book will point out, also for the first time, the use of the carpenter's square in early Christian iconography. Some experts on early Christian art and architecture such as Joseph Strzygowski believe that the early ground plan for church design (the cross-in-square plan also known as the quincunx) was based on oriental influences. There can be no doubt of the Luo Shu influence on Chinese temple design, feng shui, and geomancy. Did the Luo Shu influence early Christian church design? Was there an earlier connection between the Chinese and early Christianity than previously thought?

These are the exciting questions that my book and blog will attempt to answer. But the story does not stop here. The Luo Shu was an important influence during the Italian Renaissance when artists, architects, and mathematicians were re-discovering the wisdom possessed by the ancients. Luca Pacioli, who was a roommate and teacher of Leonardo da Vinci, was known to be an avid magic square enthusiast. Was the Luo Shu an influence on Leonardo da Vinci, Donato Bramante, Albrecht Durer and other great artists, mathematicians, and architects? And finally, were the Jesuits (who infiltrated China as early as the sixteenth century) after early Chinese documentation of the Luo Shu? The art works of Athanasius Kircher (mid 1650s) and Ferdinand Verbiest (late 1660s) suggest with certainty the Jesuits were keenly interested in the Luo Shu.

Needless to say, the Luo Shu geometric pattern was used prolifically by the early church in the same manner as the early Chinese. This book will attempt to prove with mathematical certainty that the magic square was the geometric model used on the covers of several Christian manuscripts. If this is true, then the magic square was a part of Christian iconography as early as the eighth century, thus pushing back the timeline by five hundred years when the magic square made its western appearance.

Following the story of the Luo Shu is like following the evolution of humankind over the course of thousands of years, weaving its way through many cultures who were advanced in the arts and were seeking spiritual harmony thru mathematics. Much of this knowledge has been lost over time and much is considered "secret". This is the book that explains the secret language of numbers, the language of Heaven that was gifted to us humans for the advancement of humankind.

For the benefit of those new to this site, this post will serve as an introduction to this blog and to my book, Number Time Archetype. Please understand that this is an ongoing effort that is now entering its thirteenth year.

Galileo once remarked that the world is a book written in mathematical language alluding to the theory that the mysteries of nature can be solved by simply examining the math. Throughout modern history geniuses such as Plato, Pythagoras, Da Vinci, Durer, Galileo, Newton, and Leibniz acknowledged that mathematics was necessary for the evolution and prosperity of humankind.

However, the world of math could only begin with the advent of numbers. Therefore, a numbering system would be the impetus of human evolution and prosperity.

Numbers are a language unto themselves at the ready to impart wisdom upon humankind for the purpose of evolving and prospering. The language of numbers would provide humankind with the tools and mathematical formulas to manage time and space: time as in the numbers of the calendar and space as in the Pythagorean Theorem. The arrangement of numbers into squares would reveal this information. These squares of numbers are called magic squares. The following represents the simplest magic square:

The Chinese 3x3 magic square known as the Luo Shu.

Note that all the rows, columns, and diagonals add to fifteen, the magic constant.

This arrangement of the first nine numbers would become the Chinese model to impart a perfect cosmic order to space of political or religious importance such as space dedicated to temple design, city planning, royal tomb design, and agricultural ceremonies in traditions that would last over a two thousand five hundred year period. As the Chinese were the most advanced civilization during this time (about 1,000 BC to 1,500 AD) and because math is the root basis of the technology of such supremacy, insights into the Luo Shu can access a portal into the Chinese reverence for numbers as well as the math that led to the conquering of time and space.

The concept of number was so critical to the success of humankind that the early Chinese incorporated the iconography related to math, astronomy, and agriculture into the pictographs and glyphs of the Chinese language. The combination of pictographs with subtle messages of morality (that is, tradition) built in to the glyphs would form a comprehensive model of writing which would allow the political administrative state a psychological control of authority over a population through the use of language. With symbolic pictographs, the Chinese language tells a story of a society's advancement and makes correspondences to the role of humankind in relation to Heaven and earth for the benefit of agriculture that emphasizes a moral tradition or a moral code of conduct. Math would prove to be the foundation of this advancement and played a significant role in language symbolism.

As the 3x3 magic square grid is the root origin of such important Chinese words such as qu (old style: 曲) = the carpenter's square and music, tien (典) = a rule, canon, xing = to rise, to prosper, jing (井) = well (water), and ya (亞) = the cosmic center; it becomes apparent that the Luo Shu magic square and the concept of "number" were sacred and played an important role in the philosophy of the Chinese language, which uses the Luo Shu pattern of nine to help establish order over chaos through the use of math and tradition.

As the 3x3 magic square grid is the root origin of such important Chinese words such as qu (old style: 曲) = the carpenter's square and music, tien (典) = a rule, canon, xing = to rise, to prosper, jing (井) = well (water), and ya (亞) = the cosmic center; it becomes apparent that the Luo Shu magic square and the concept of "number" were sacred and played an important role in the philosophy of the Chinese language, which uses the Luo Shu pattern of nine to help establish order over chaos through the use of math and tradition.

Unlike the western system of treating numbers strictly as numerical entities to be manipulated by formulas, the Chinese philosophy of numbers (number) would correspond to various numerical systems intended to impart cosmic order. Magic squares represented an ideal number system and were an important source for these "cosmic" or "sacred" numbers. For instance, the center in the Chinese system and the center number in Luo Shu magic squares represent several significant concepts. The center represents the axis mundi or where the four cardinal directions meet. It is considered the meeting place of Heaven and earth, a most important concept in temple design. The center of a Luo Shu magic square also represents the axis mundi and can be calculated by the following method:

Let x equal any odd number greater than 1, then

These numbers will always be part of a Pythagorean triplet as well as being "centered" numbers making these numbers doubly significant. For example, if x is 7, then the center between one and 49 is 25 which is part of the 7-24-25 Pythagorean Triad. In other words, x and the center number are the two odd components of the Pythagorean triplet. (In the Pythagorean and Chinese numerology systems, odd numbers are superior to even numbers, this would be one reason why.)

Example: the 7x7 magic square and some of the features unique to magic squares in the Luo Shu format.

Example: the 7x7 magic square and some of the features unique to magic squares in the Luo Shu format.

x = the size of square = 7

y = the center = 25

magic constant = (x)(y) = 175

∑x = ∑7 = 28

∑x2 = ∑49 = x2y = 1,225

note the cross of odd numbers that run thru the horizontal and vertical axis

y = the center = 25

magic constant = (x)(y) = 175

∑x = ∑7 = 28

∑x2 = ∑49 = x2y = 1,225

note the cross of odd numbers that run thru the horizontal and vertical axis

The Pythagorean Theorem served as the mathematical backbone for the understanding and ordering of the cosmos, as well as land surveying and water management on the terrestrial earth. The importance of the Pythagorean Theorem cannot be understated and was thusly recognized by the early Chinese as its symbol, the carpenter's square, shoulders the legacy as one of the most important icons in Chinese philosophy. In language, the use of the Chinese character for carpenter's square ju, 矩, when combined with the Chinese character for compass gui, 規, forms a new word, gui ju, 規矩, which means to establish order, a moral code, or the way things should be. The early Chinese placed extreme importance on the concept that to establish order a moral standard must be followed and astronomical tools and math would be essential. In art, the carpenter's square symbolism can be found in the royal tombs of kings. In astronomy, the carpenter's square also symbolized the gnomon - the most important astronomical instrument known to humankind for thousands of years.

The gnomon was simply a stick in the ground whose shadow length would determine the approximate time of year between winter and summer solstice. The painstaking tradition of measuring, recording, saving, and studying the shadow length data for thousands of years, i.e. calendar making, was part of the moral standard to evolve and prosper and was essential to the role of the king. The shadow of the gnomon was in a right angle relationship to the gnomon thereby generating a right angle whose measurements would satisfy the Pythagorean Theorem. Therefore, the gnomon, the right angle, and the carpenter's square were symbols of time and space.

The gnomon, the Luo Shu (math and the concept of number), music, and astronomical tools had special status among the early Chinese as these were instruments that helped humans to connect with Heaven for the betterment of humankind. The Luo Shu was an important element of Chinese philosophy as it represented a musical source, an astronomical correspondence, and a mathematical system that enabled the Luo Shu to become a spiritual tool to establish order and bring humankind in harmony with Heaven and earth.

The secret to the Luo Shu is the following formula that allows expansion of the 3x3 magic square into larger magic squares that all exhibit features in common but the most significant is that a Pythagorean triplet of numbers appears at the heart of each square.

|

| X = size of square

Y = X2 + 1 ÷ 2 = the center

X, Y, and Y - 1 always generate a Pythagorean triplet |

Part Two of this book looks at all the higher order magic squares which will reveal the philosophy as to why the early Chinese considered the Luo Shu the perfect model to express cosmic order.

The Chinese civilization was not the only culture to be greatly influenced by math, the concept of number, and magic squares. The Christian community, which borrowed from many cultures and religions, also was greatly influenced by Pythagorean and Chinese numerology, which share many commonalities.

The Chinese civilization was not the only culture to be greatly influenced by math, the concept of number, and magic squares. The Christian community, which borrowed from many cultures and religions, also was greatly influenced by Pythagorean and Chinese numerology, which share many commonalities.

This book will reveal for the first time the influence of the Luo Shu on early Christianity. There is no question that monks from as early as the eighth century were incorporating magic square symbolism onto the covers of some of the worlds' most valuable books. This blog and book will point out, also for the first time, the use of the carpenter's square in early Christian iconography. Some experts on early Christian art and architecture such as Joseph Strzygowski believe that the early ground plan for church design (the cross-in-square plan also known as the quincunx) was based on oriental influences. There can be no doubt of the Luo Shu influence on Chinese temple design, feng shui, and geomancy. Did the Luo Shu influence early Christian church design? Was there an earlier connection between the Chinese and early Christianity than previously thought?

These are the exciting questions that my book and blog will attempt to answer. But the story does not stop here. The Luo Shu was an important influence during the Italian Renaissance when artists, architects, and mathematicians were re-discovering the wisdom possessed by the ancients. Luca Pacioli, who was a roommate and teacher of Leonardo da Vinci, was known to be an avid magic square enthusiast. Was the Luo Shu an influence on Leonardo da Vinci, Donato Bramante, Albrecht Durer and other great artists, mathematicians, and architects? And finally, were the Jesuits (who infiltrated China as early as the sixteenth century) after early Chinese documentation of the Luo Shu? The art works of Athanasius Kircher (mid 1650s) and Ferdinand Verbiest (late 1660s) suggest with certainty the Jesuits were keenly interested in the Luo Shu.

Needless to say, the Luo Shu geometric pattern was used prolifically by the early church in the same manner as the early Chinese. This book will attempt to prove with mathematical certainty that the magic square was the geometric model used on the covers of several Christian manuscripts. If this is true, then the magic square was a part of Christian iconography as early as the eighth century, thus pushing back the timeline by five hundred years when the magic square made its western appearance.

Following the story of the Luo Shu is like following the evolution of humankind over the course of thousands of years, weaving its way through many cultures who were advanced in the arts and were seeking spiritual harmony thru mathematics. Much of this knowledge has been lost over time and much is considered "secret". This is the book that explains the secret language of numbers, the language of Heaven that was gifted to us humans for the advancement of humankind.

ONLY $36.50